Saturday, December 27, 2014

Thursday, December 25, 2014

Wednesday, December 24, 2014

Tuesday, December 23, 2014

Tuesday, December 16, 2014

Neither Derivative Nor Eclectic

In the end Emerson would prove to be more than an American Plato since he would reject Plato's politics and would struggle to reconcile Platonism with democratic idealism. He is not just an American popularizer of Kant either, because he subjected German idealism to what may be called the critique of everyday life and because he brought life to Kant's acceptance of the authority of subjective knowledge by connecting it with the experiences of the great religious mystics and enthusiasts and with the passions and raptures of great poetry. Nor is Emerson merely an American Marcus Aurelius, because he reconciles classical Stoic insistence on self-rule with Dionysian wildness and a sweeping commitment to self-expression. Emerson is at least neither derivative nor eclectic. His insistence on grounding thought, action, ethics, religion, and art in individual experience is his center. He makes a modern case for the idea that the mind common to the universe is disclosed to each individual through his or her own nature. In this respect, Plato is a Greek premonition of Emerson, Marcus Aurelius a Roman one, and Kant a German one.

--Richardson, Emerson: The Mind On Fire, 234.

Tuesday, December 9, 2014

Emerson, Tolstoy, and Post-Christian Theism

In a sermon preached on May 27, 1832, Ralph Waldo Emerson told his congregation, "I regard it as the irresistible effect of the Copernican astronomy to have made the theological scheme of redemption absolutely incredible." Robert Richardson comments:

"Emerson's preference for astronomy over conventional Christian theology constitutes his break with the church. It is not a break with theism, not a rejection of the religious view of the world. It is a specific rejection of the idea that the center of Christianity is the fall of humankind in Adam and Eve and the redemption of humanity through the sacrifice of Christ." Richardson, Emerson: The Mind On Fire, 124-125.

Regrettably, Emerson was wrong to think that the fall of humankind and its redemption through the crucifixion of Christ is not the "center of Christianity"--it is the center, theologically speaking and, in my view, he was right to reject it. Like his admirer Tolstoy, Emerson was a post-Christian theist who thought himself a "true" Christian. Hence, he had no choice but to leave the church (and, by the same token, Russian Orthodoxy had no choice but to excommunicate Tolstoy).

Sunday, December 7, 2014

Saturday, December 6, 2014

Whence Is Your Power?

From my nonconformity. I never listened to your people's law, or to what they call their gospel, and wasted my time. I was content with the simple rural poverty of my own. Hence this sweetness.

--Ralph Waldo Emerson (Journal entry: see Richardson, The Mind On Fire, 4).

Thursday, December 4, 2014

Wednesday, December 3, 2014

The Broken Covenant

In 1992, when I received a flyer from the University of Chicago Press announcing the publication of the second edition of Robert Bellah's The Broken Covenant: American Civil Religion in Time of Trial, I ordered a copy on the spot. I had never read the first edition nor anything else by Bellah at that point. In fact, I'd never heard of the book and had no idea what it was about. But I had a feeling...

The book exceeded all of my expectations and became something of a political handbook for me throughout the 1990's. Nothing Bellah wrote before or after it has had the same effect on me--in fact, I generally found his post-TBC work disappointing. It was almost as if he had embarrassed himself by writing such a stirring "jeremiad" (his word) and was determined never to repeat that mistake. Maybe I should be more charitable, because I owe him so much from this one book; nevertheless, I cannot help but think that what happened to him in its wake was nothing less than a failure of nerve.

Recent events have compelled me to pick up the book again. As I re-read it, I am stunned once more by Bellah's masterful juxtapositions of American Myth and the historical record. For my money, this is religious studies at its best: timely, insightful, self-critical. The Broken Covenant deserves to be considered a classic. If we neglect it, we do so to our shame.

Sunday, November 30, 2014

"My Own Quarrel With America"

After a conversation with Henry Thoreau in October 1850, Emerson recorded in his journal: "My own quarrel with America, of course, was, that the geography is sublime, but the men are not." He then noted that those who had joined Atlantic to Pacific had done so through "selfishness, fraud, & conspiracy." Gay Wilson Allen, Waldo Emerson (1981), 545.

Nothing has changed.

Saturday, November 29, 2014

Thursday, November 27, 2014

Fly The Blue Flag!

A plain blue flag serves as the banner of the Invisible Whitmanian Republic: a non-state subsisting within the travesty that is the militarized corporatocracy calling itself the United States of America.

It is a declaration of difference, of The Great Refusal, of the determination not to be counted among the sublimated slaves of post-industrial civilization--those who have been enslaved "neither by obedience nor by hardness of labor but by the status of being a mere instrument," reduced to the state of a thing. (see H. Marcuse, One Dimensional Man, 32-33).

Declare your independence and your difference: on national holidays and occasions of state, on July 21 (the date of Emerson's letter to Whitman congratulating him on the first edition of Leaves of Grass), and on any date you damn well please:

Fly the blue flag and RESIST, REFUSE, RENOUNCE the violent consumerist catastrophe that now plagues the world.

Show your loyalty to the country's refounders: Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman.

Fly the blue flag!

Wednesday, November 26, 2014

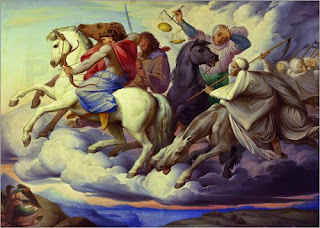

The Four Horsemen

If people really understood how the justice system operates, they would know that the cop in the Michael Brown case should not have been called to testify as a material witness to the crime that the Grand Jury was investigating--since he was the prime suspect. This is NEVER done--except, of course, when you want to confuse the Grand Jury into thinking that their job is to decide on guilt or innocence instead of whether or not there is sufficient evidence for an indictment.

We should expect riots in every American city right now--only, that won't happen, because the Administrative State has the One Dimensional society under its thumb. Meanwhile, China's economic troubles might just kick off a global financial collapse in the coming year.

I hear the pounding of the hooves...

Monday, November 24, 2014

Michael Brown

All Americans must begin to make the connection between the violence we export and the violence we produce for "domestic consumption."

And all should take note that, in both cases, the victims are the poor and people of color.

And, no, I don't think it's a coincidence; I think it's a cancer.

Saturday, November 22, 2014

Friday, November 21, 2014

Tuesday, November 18, 2014

Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

In reading the history of nations, we find that, like individuals, they have their whims and their peculiarities; their seasons of excitement and recklessness, when they care not what they do. We find that whole communities suddenly fix their minds upon one object, and go mad in its pursuit; that millions of people become simultaneously impressed with one delusion, and run after it, till their attention is caught by some new folly more captivating than the first. We see one nation suddenly seized, from its highest to its lowest members, with a fierce desire of military glory; another as suddenly becoming crazed upon a religious scruple; and neither of them recovering its senses until it has shed rivers of blood and sowed a harvest of groans and tears, to be reaped by its posterity. At an early age in the annals of Europe its population lost their wits about the sepulchre of Jesus, and crowded in frenzied multitudes to the Holy Land; another age went mad for fear of the devil, and offered up hundreds of thousands of victims to the delusion of witchcraft. At another time, the many became crazed on the subject of the philosopher's stone, and committed follies till then unheard of in the pursuit. It was once thought a venial offence, in very many countries of Europe, to destroy an enemy by slow poison. Persons who would have revolted at the idea of stabbing a man to the heart, drugged his pottage without scruple. Ladies of gentle birth and manners caught the contagion of murder, until poisoning, under their auspices, became quite fashionable. Some delusions, though notorious to all the world, have subsisted for ages, flourishing as widely among civilised and polished nations as among the early barbarians with whom they originated,--that of duelling, for instance, and the belief in omens and divination of the future, which seem to defy the progress of knowledge to eradicate them entirely from the popular mind. Money, again, has often been a cause of the delusion of multitudes. Sober nations have all at once become desperate gamblers, and risked almost their existence upon the turn of a piece of paper. To trace the history of the most prominent of these delusions is the object of the present pages.

Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, and one by one.

--Charles Mackay

Friday, November 14, 2014

The Fixer

"All men are Jews, though few men know it." --Bernard Malamud

Lately, I have been re-reading Bernard Malamud's stunningly memorable novel The Fixer (1966). I say "stunningly memorable" because I first read it in 1977 (the Fall semester of my senior year in high school). I have not read it since. And yet, picking it up again in 2014, I recall scene after vivid scene--as if I had read the book just recently. And I recall, as well, my own confusion as a white Protestant and reasonably affluent seventeen year-old male who was being exposed, for the first time, to the reality of rabid anti-semitism.

Growing up during the high tide of the civil rights era, I had been sensitized to the plight of people of color living in the United States as second or third class citizens. But Jews? I thought of the Jews I knew--and, granted, my exposure at that point in my life was fairly narrow--as privileged white people like myself. And so they were; what they were not was Christian. At the time, I did not see why that fact should occasion intense hatred of Jews by Christians (and still don't) and so, although I was aware that anti-semitism existed, I regarded it as an anomaly--like Nazi Germany. And, like Nazi Germany, I regarded it also as largely a thing of the past.

Malamud's novel brilliantly evokes how bigotry, superstition, and modern scientific rationality sat together quite comfortably in 19th century Russian society and, when combined with the Czarist state's legal bureaucracy, could create a tidal wave of blind cruelty capable of crashing down on an unsuspecting life: in this case, the life of one Yakov Bok, an impoverished handyman who, though born to Jewish parents, considered himself a "free thinker" in the mold of Spinoza, and left his native village amidst the wreckage of a bad marriage in the hope of starting fresh (and passing as a gentile) in Kiev.

And therein lies the true genius of the novel: for, try as he might, Bok cannot escape his Jewishness because it is thrust upon him repeatedly throughout the story--not by fellow Jews, but by the gentiles who wish to see him suffer because he had the temerity to be born to the "wrong" parents. This insanity--for there is no other word for it--is a brokenness that the fixer cannot fix.

In Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, Richard Rorty argued that part of our moral education as Americans at the close of the 20th century should include books that "help us become less cruel." (CIS, 141). He does not mention Malamud's The Fixer, but it would have made a superb example of the kind of book he had in mind.

And at the beginning of the 21st century, with Muslims now filling the social role of the "new Jews" in the U.S. and elsewhere, Malamud's book is as relevant a read as ever.

Saturday, November 8, 2014

My Own Private Mt. Rushmore

On my own private Mt. Rushmore, I continually carve the faces of Emerson, Thoreau, Whitman, and Melville...

Tuesday, November 4, 2014

Monday, November 3, 2014

American Midrash

In my obsessive-compulsive reading habits, I return again and again to American literature; I suppose I do this because I fear that, if I don't, I will reach the point where I decide that there is nothing redeemable about this country.

I began to read Emerson and Thoreau early--the latter at age 13, the former a little later, around 16 or 17. In any event, it was at such an impressionable age that they continue to think through me. I cannot escape them (though I've tried) and am learning to reconcile myself to that fact. It's not that hard, really. Father Emerson rattles on through Thoreau and Whitman, Wallace Stevens and Frost, but also Nietzsche and Tolstoy and, as fate would have it, Norman O. Brown.

Word-madness is the gift of the gods. If we remember to drink deep at the well of language, we may fortify ourselves against the Orwellian Newspeak with which we are daily inundated. Stay close to the Logos and you remain connected to the Over-Soul. Lose touch with that and you risk being turned into a monster: just another one-dimensional zombie wandering through the consumer-capitalist Apocalypse.

Saturday, November 1, 2014

The Invisible Republic We Hold In Our Hearts

I claim as kin father Emerson, brother Thoreau, and weird uncle Walt, but friends and neighbors abound.

Old man Melville lives in the big house high on the hill, overlooking the port, while Billy Faulkner, displaced scion of the old south, haunts the dirty bars down by the docks.

And what of Tecumseh, and Frederick Douglass? We feel their presence in the streets and alleyways, but we should be walking next to them, side by side. Such is the state of our American exile.

Emily Dickinson is but a silhouette against the shade of a window that looks out on Main Street when the shutters are not closed. Woody Guthrie, whooping like a wild bird on the street corner, keeps his guitar case open for loose change. Mr. Stevens, solemn at his desk, shuffles papers while dreaming in tropical hues. Jack London pilots a skiff in the bay; Robinson Jeffers buys a ticket at the station for the first train headed west.

Henry Miller, uncle Walt's sketchy disciple, and yet a genius all the same, goes out for drinks with the bearded lady when the circus is in town. And moody Tom Wolfe, lately from Chapel Hill, tries his hand at playwriting at the kitchen table of his mother's boarding house while old Sam Clemons smokes a cigar outside the bank and cracks rueful jokes under his breath.

This is but a small sample of the dramatis personae who populate the Invisible Republic we hold in our hearts.

Friday, October 31, 2014

From "Terminus"

As the bird trims her to the gale,

I trim myself to the storm of time,

I man the rudder, reef the sail,

Obey the voice at eve obeyed at prime:

"Lowly faithful, banish fear,

Right onward drive unharmed;

The port, well worth the cruise, is near,

And every wave is charmed."

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Wednesday, October 29, 2014

Monday, October 20, 2014

Socrates

As an undergraduate classics major, I translated Plato's Apologia. When I completed the translation I sat back and asked myself, "How is it possible that no one created a religion around this man?"

Wrong time, wrong place. Otherwise, we'd have churches of Socrates throughout the world. Only it wouldn't be Socrates, but some evangelist's pious misrepresentation of his teachings and significance.

Thank God, I say, thank God! For if he had not been spared such misplaced adoration, we would have lost him forever.

Sunday, October 19, 2014

The People, Yes, The People

The totalitarian tendencies of the one-dimensional society render the traditional ways and means of protest ineffective--perhaps even dangerous because they preserve the illusion of popular sovereignty. This illusion contains some truth: "the people," previously the ferment of social change, have "moved up" to become the ferment of social cohesion. Here rather than in the redistribution of wealth and equalization of classes is the new stratification characteristic of advanced industrial society.

Herbert Marcuse, ODM, 256.

Sunday, October 12, 2014

Van Gogh's "Theology"

As articulated by Norman O. Brown: "The movement of energy on the earth--from geophysics to political economy, by way of sociology, history, and biology--all manifests that universal effervescence of superfluous prodigality which is best honored as a god or as God. Science becomes religious in deference to the awesome facts." Dionysus in 1990.

Friday, October 10, 2014

Thursday, October 9, 2014

Walter Kaufmann Revisited

I was a sophomore in college in September 1980 when Walter Kaufmann passed away. I wore a black armband in remembrance.

I often feel that, before anyone engages in a conversation about religion, they should first read Kaufmann's Critique of Religion and Philosophy and The Faith of a Heretic. At that point, an intelligent discussion can proceed.

Saturday, October 4, 2014

Dear Theo

In my early twenties, upon the insistence of my oldest brother, I checked out from my local library a copy of Dear Theo, the letters of Vincent Van Gogh to his brother (as collected and edited by Irving Stone; the complete collection is now available online here).

I did not sit down and read the letters straight through. I found that, whenever I picked up the book, it was like grasping hold of a live wire and I rarely got away without a shock. So, instead, I dipped into the volume from time to time (and, when I would visit my brother in Philadelphia, I would occasionally consult his copy). I knew then, without a doubt, that the letters belonged to world literature; some of them, to world religious literature.

While in Paris in September (2014), I began to work my way through the Penguin Classics edition of Van Gogh's letters (published in the mid-1990's). Like Stone's Dear Theo, the Penguin edition offers a selection, but one that reflects a scholarly (rather than a novelistic) perspective. I value both--but prefer Stone's Lust for Life to his Dear Theo because the former does not purport to be Van Gogh's "autobiography."

Although it is possible to read the letters apart from the artist's work, I think that they need to be viewed as part of the artist's total oeuvre; over a ten year period, Van Gogh created an amazing portfolio of words and images. When one encounters him in both media, his genius is made visible.

Thursday, October 2, 2014

Heidegger In Black

More bad news from the Heidegger front: Peter E. Gordon's review essay in the NYRB, October 9, 2014.

Saturday, September 27, 2014

Humanity's Debt To Paris

Paris is a living reminder of what can happen when a city embraces the notion that aesthetics ought not to be an afterthought.

Wednesday, September 24, 2014

Tuesday, September 16, 2014

Saidian and Rortian Humanitas

In The World, the Text, and the Critic, the late Edward Said restates the three pillars of humanitas (cosmos, logos, and skepsis). Moreover, he extends the notion of skepsis beyond its definition (a suspension of final judgment upon matters where the available data simply does not warrant such finality) to its embodiment in critical practice: "...criticism must think of itself as life-enhancing and constitutively opposed to every form of tyranny, domination, and abuse; its social goals are noncoercive knowledge produced in the interests of human freedom" [WT&C, 29].

It is no accident, by the way, that Saidian humanitas corresponds (nicely) with Rortian (where we find the concern for "the world" expressed as "solidarity," the concern for "the text" expressed as "contingency"--for all textual meaning is context dependent--and the concern for "the critic" expressed as "irony"--a word Said recommends that we couple with "criticism" [WT&C, 29]).

This correspondence is due to the fact that Saidian and Rortian humanitas are genuine modes of that peculiar disposition or orientation--where the genuine article is distinguished from "false friends" by reference to the confluence of its three pillars.

Heidegger's maddening Letter on Humanism aside, genuine humanitas is (and has always been) an orientation predicated upon cosmos, logos, and skepsis. The struggle with metaphysics--if it is even necessary--is but a side-show and a distraction. As Rorty reminds us in his late appreciation of Gadamer: "being that can be understood is language."

Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

Monday, September 15, 2014

Humanitas

The three pillars of humanitas (or humanism) are cosmos, skepsis, and logos. An individual becomes a humanist because s/he is gripped by a fascination for the mysterium or "elusive something" that seems to pervade human life. What does it mean to be a human being? That is the pervasive mystery. The fact that one might find him/herself at leisure to ponder such a question says a lot about the conditions under which humanism becomes possible.

A fascination with logos is often the entrance-way to a fascination for cosmos and a tendency towards skepsis: for the workings of language, when carefully considered, confront one with the varieties of order that human beings have produced across the globe and through time; they also raise more questions than a lifetime's worth of research can possibly answer. The enormity of the task that faces the individual who embraces humanitas (i.e., making sense of human being through that most human of faculties, language) cannot be underestimated. Skepsis (or a suspension of final judgment upon matters where the available data simply does not warrant such finality) is a natural concomitant.

The fascination for cosmos (varieties of order) combined with a tendency towards skepsis produces an interesting side effect: for this combination engenders a cosmopolitanism in the humanist. Cosmopolitanism results when exposure to the implacable fact of human difference creates not fear but wonder; in the event, an individual's acceptance of difference expands and parochialism recedes proportionately.

This is humanitas.

For most humanists, the mysterium of the three pillars of humanitas (the mysterium that forged them in its smithy) fully occupies their attentions. For others, there remains the mysterium tremendum et fascinans. The former kind of humanist is nowadays referred to as a "secular humanist"; the latter is referred to as a "religious humanist." The real difference between the two kinds of humanist is that the latter tends to hold that the mysterium tremendum et fascinans in some (mysterious) way possesses the key to answering humanitas's threshold question: what does it mean to be a human being? In addition, the religious humanist tends to suspend skepsis to some degree when it comes to considering the mysterium tremendum. Philosophers have endowed skepsis about skepsis in such matters with the technical name fideism. The humanism of Montaigne is a classic example of this type.

Thursday, September 11, 2014

The Latter Day Vagabond Scholar

It is the fate of the vagabond scholar to be sacrificed on the altar of the ideal of disinterestedness. That is, in fact, our special calling. We are intellectual wanderers who demonstrate to others, by the kinds of questions that we ask, how it is possible to think the taboo--the otherwise unthinkable.

In thinking the otherwise unthinkable, we expand the universe of possible discourse. This is our service to humanity: we set ourselves the task of breaking silences where silences have been imposed in order to insure intellectual and (via the intellect) social conformity.

We are perpetual heretics, forever frustrating the peace of mind that orthodoxies promise. We are both the products of modernity and its facilitators--for modernity, as Peter Berger taught us long ago, "multiplies choices and concomitantly reduces the scope of what is experienced as destiny. In the matter of religion, as indeed in other areas of human life and thought, this means that the modern individual is faced not just with the opportunity but with the necessity to make choices as to his beliefs. This fact constitutes the heretical imperative in the contemporary situation. Thus heresy, once the occupation of marginal and eccentric types, has become a much more general condition; indeed, heresy has become universalized" [Berger, The Heretical Imperative (1979), 28].

Or so it appeared to sociologists of religion in the 1970's. We are a long way from the halcyon days of free thought and heresy has once again become the occupation of the marginal and eccentric. No matter. We follow our imam: Socrates.

Sunday, September 7, 2014

Saturday, September 6, 2014

Why And How To Read The Bible

Norman Gottwald is a pioneering Marxist Biblical scholar--a distinction shared by far too few in his profession.

In my view, there are two reasons to read the Bible: the first is for aesthetics (that of the Biblical texts themselves and of the vast body of art and literature upon which they have left their impact), and the second is for its utopianism (the Bible's major contribution to the Near Eastern prophetic tradition).

While it is true that most Marxian social and economic categories belong to an industrial era and are not an exact fit for the prevailing conditions of ancient Israel, they are quite suggestive and shed light upon the problems of equality/inequality and liberation/bondage--problems that are not unique to modern societies but have plagued human communities around the globe for as long as human beings have lived in them.

Reading Gottwald, one is never very far from these issues--and that is a good thing, because too many people turn to the Bible in order to escape them.

Tuesday, September 2, 2014

The Sublime Summit of Literature in English...

is still shared by Shakespeare and the King James Bible.

--Harold Bloom, The Shadow of a Great Rock (2011), 1.

Even a litany of locusts such as that found in the prophecy of Joel--singing of agricultural devastation wrought by insects--possesses a beguiling sonority:

That which the palmerworm hath left hath the locust eaten; and that which the locust hath left hath the cankerworm eaten; and that which the cankerworm hath left hath the caterpiller eaten. (Joel 1:4).

"The largest aesthetic paradox of the KJB," writes Bloom, "is its gorgeous exfoliation of the Hebrew original. Evidently the KJB men knew just enough Hebrew to catch the words but not the original music. Their relative ignorance transmuted into splendor because they shared a sense of literary decorum that all subsequent translators seem to lack." SGR, 12.

Amen and amen.

Friday, August 29, 2014

Existentialism Is A Mysticism

"Nothingness lies coiled the heart of being--like a worm." Jean-Paul Sartre, Being and Nothingness, tr. Hazel Barnes, p. 56.

Thursday, August 28, 2014

Wednesday, August 27, 2014

Below Freshet and Frost and Fire

"Let us settle ourselves, and work and wedge our feet downward through the mud and slush of opinion, and prejudice, and tradition, and delusion, and appearance, that alluvion which covers the globe, through Paris and London, through New York and Boston and Concord, through church and state, through poetry and philosophy and religion, till we come to a hard bottom and rocks in place, which we can call reality, and say, This is, and no mistake; and then begin, having a point d'appui, below freshet and frost and fire, a place where you might found a wall or a state, or set a lamp-post safely, or perhaps a gauge, not a Nilometer, but a Realometer, that future ages might know how deep a freshet of shams and appearances had gathered from time to time."

Henry David Thoreau, American Dervish

"Where I lived," Walden.

Tuesday, August 26, 2014

Thursday, August 21, 2014

Fecundity In Three Acts

Act One: The Burgeoning Branches.

Act Two: The Venus of Willendorf.

Act Three: Existential Reflection.

Monday, August 18, 2014

Saturday, August 16, 2014

Wednesday, August 13, 2014

American Transcendentalism's Worthy Successor

I was raised by unconscious Calvinists. In my late teens, I decided to investigate Calvinism and to make explicit and conscious for myself what had been hitherto implicit and unconscious. Claustrophobia quickly set in. My discovery of Jonathan Edwards provided some relief--with his notion of "the sense of the heart"--after all he was, in the words of Morton White, "like St. Augustine...a mystic who could argue."

In the end, however, I chose Kierkegaardian faith-as-passion and Bonhoeffer's late humanism over Edwards since the latter still found it necessary to come to Calvinism's defense.

Over time (and after reading Ghazali in the mid-1990's), faith-as-passion transmuted into the religion of longing (tasawwuf) and Bonhoeffer's Menschlichkeit evolved into Camus's "profound and radical this-worldliness [combined] with an explicit rejection of traditional Christian theodicy" [James Woelfel, Bonhoeffer's Theology, 28].

Although I invoke Camus, it is Henry Miller's essay "The Wisdom of the Heart" that contains a precise formula of the position I had come to by my junior year in college:

The whole secret of salvation hinges on the conversion of word to deed, with and through the whole being. It is this turning in wholeness and faith, conversion, in the spiritual sense, which is the mystical dynamic of the fourth-dimensional view. I used the word salvation a moment ago, but salvation, like fear or death, when it is accepted and experienced, is no longer "salvation." There is no salvation, really, only infinite realms of experience providing more and more tests, demanding more and more faith.

Miller was the self-conscious disciple of Whitman and, as such, offered in his "fourth-dimensional view" or "wisdom of the heart" a worthy successor to American Transcendentalism.

Tuesday, August 12, 2014

The Illegitimate Fourth Estate

"To a philosopher all news, as it is called, is gossip, and they who edit and read it are old women over their tea...By closing the eyes and slumbering, and consenting to be deceived by shows, men establish and confirm their daily life of routine and habit everywhere, which still is built on illusory foundations."

Henry David Thoreau

American Dervish

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)