Friday, May 23, 2014

Perennial Heideggerian Frustrations

D. F. Krell points to Heidegger's own awareness of "the surreptitious predominance [in Being and Time] of certain forms of thought and language rooted in the metaphysical tradition" that he claimed to be bringing to an end, "such as the idea of 'fundamental ontology' or the readily adopted translation 'truth' for aletheia" (Martin Heidegger: Basic Writings, 33).

Though aware of the problem, Heidegger never adequately addressed it. As a consequence, there are those who find in Being and Time cover for their own metaphysical agendas.

And then there is, of course, that brief period of about 10 months or so when he allowed himself to be seduced by the excitement of National Socialism--an error, in retrospect, of ghastly proportions.

Krell notes: "That his early engagement in the Nazi cause was a monstrous error all concede; that his silence [after the war regarding Nazi atrocities committed during the war] is profoundly disturbing all agree; whether that error and the silence sprang from basic and perdurant tendencies of his thought remains a matter of bitter debate" (ibid., 28).

One can certainly find suggestive clues in Heidegger's thought that potentially point the way to his enthusiasm for Hitler's movement: a deep thread of political conservatism may be detected in some of his writings. Then again, one could interpret Heidegger as on a path parallel to Tolstoy's.

These are perennial Heideggerian frustrations that defy resolution.

Thursday, May 22, 2014

Reflections upon the Flaw in Heidegger's Byzantine "Golden Bowl"

Martin Heidegger's obsession with "origins" and "primordiality" undercuts his insistence upon "existential authenticity." This is an unresolved conflict that runs throughout the body of his work, becoming ever more pronounced as time goes on. It is the worm in the Heideggerian apple, the flaw in his Byzantine "Golden Bowl." While purporting to release us from the demands of the "One" or the "They" (depending upon the translation), the freedom that Heidegger promises whenever he moves beyond the bald assertion that Dasein's "authentic" nature is "revealed" as "thrown" is significantly gerrymandered by his claim to have "recovered" or "disclosed" the "authentic" nature of being-in-the-world. It is understandably unsatisfying to be left with "thrownness," but it is equally troubling to find oneself manipulated in the direction of someone else's idea of "authenticity." So much for liberation from the "They."

One can hear his own deep (and prudent) anxieties about self-creation "speak" from his texts. It is difficult to imagine that this is the song he would have us hear. There is much bluff in Heidegger's oracular prose. He is a man who whistled, compulsively, whenever he passed a graveyard. He counseled resolve in the face of death; did he achieve it?

I do not wish these reflections to be regarded as mere ad hominem attack. At 16, I first encountered Heidegger in William Barrett's Irrational Man and was seduced by many of his ideas; every few years I return to his writings and the scholarly commentary on them; I puzzle through them again and again. At this point in my life, I think it fair to say that I am "stuck" with Heidegger. That said, I will not dishonor him with sycophancy.

Tuesday, May 20, 2014

Sunday, May 18, 2014

Heidegger and Wittgenstein

Like Kant, Heidegger and Wittgenstein attempt to determine whether the relation between Knowing and Being is rendered more intelligible by seeing to what extent things conform to our language and mode of understanding. Being and Time and the Philosophical Investigations mark the crest of the second wave of Kant's Copernican Revolution. In their works Heidegger and Wittgenstein find themselves forced to reject the model of knowledge that has been most prominent throughout the history of philosophy.

Ross Mandel, "Heidegger and Wittgenstein: A Second Kantian Revolution," in Heidegger & Modern Philosophy, edited by Michael Murray (Yale University Press, 1978), 259.

Friday, May 16, 2014

Heidegger and Ibn 'Arabi

As Henry Corbin discovered many decades ago, fascinating resonances obtain between the writings of Ibn 'Arabi and Martin Heidegger. The differences between the two thinkers ought not to be ignored, however, and may be attributed to a variety of factors. While both thinkers were heir to the history of European philosophy, Ibn 'Arabi had the "advantage" (if you will) of inheriting less of it than did his German counterpart and, in any case, he didn't feel himself under any obligation to answer to or for that inheritance.

Another salient difference is that Heidegger arrived upon the philosophical scene after the death of God; in Ibn 'Arabi's world and time, God was still very much alive.

Thursday, May 15, 2014

Heidegger Revisted

For Martin Heidegger, "[t]he font of genuine thought is astonishment, astonishment at and before being. Its unfolding is that careful translation of astonishment into action which is questioning. For Heidegger, there is a fatal continuity between the assertive, predicative, definitional, classificatory idiom of Western metaphysics and that will to rational-technological mastery over life which he calls nihilism...In Heidegger's 'questioning of being,' an activity so central that it defines, or should define, the humane status of man, there is neither enforcement nor a programmatic thrust from inquisition to reply (a thrust unmistakably encoded in syllogistic and formal logic). To question truly is to enter into harmonic concordance with that which is being questioned. Far from being initiator and sole master of the encounter, as Socrates, Descartes, and the modern scientist-technologist so invariably are, the Heideggerian asker lays himself open to that which is being questioned and becomes the vulnerable locus, the permeable space of its disclosure."

--George Steiner, Martin Heidegger (1989), 54-55.

Sunday, May 11, 2014

R. A. Nicholson, Orientalist (d. 1945)

Reynold Nicholson's The Mystics of Islam was among the first Orientalist works I read seriously when I began to investigate aspects of the Islamic tradition twenty years ago. What I found in Nicholson was exceptional erudition combined with profound anxieties about his subject: the British scholar was determined to resist the pull of Muslim pietism that he clearly understood and, at unguarded moments in his text, approved. In order to contain his own enthusiasm, he poisoned the well of his exegesis of previously unavailable Arabic and Persian works with condescending observations about the inability of the "Oriental mind" (unlike the European) to recognize clear contradiction (p. 130), or to appreciate the subtleties of "natural law" (p. 139). I did not have to read Edward Said to take exception to such remarks: Nicholson's mixture of scholarship and bigotry left me admiring of the former and disgusted with the latter. The passage of time has not made his defects any easier to swallow. Such is the legacy of Orientalism: it serves to remind us that, among the roots of racism, is repressed envy.

Saturday, May 3, 2014

Heraclitus of Ephesus

"...Heraclitus will always be right in this, that being is an empty fiction."

--F. Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols.

Friday, May 2, 2014

Attar, d. 1220 CE

Farid-ud-Din Attar "left to posterity a great many epic poems most of which are stories within a story, a frame story with small tales in it. Many of the heroes of these small tales belong to the poorest and lowest social class: beggars, fools, and sufis, who mostly also belong to a low social stratum. In the poems of Attar, these poor people are allowed to speak for the first time in Persian poetry. Before the time of Attar, poetry was centered in the courts of the kings; it reflected the world and the interests of the emirs and sultans. There is no doubt that it is sufism that gave the lower classes a new self-consciousness, which allowed them to open their mouths and to speak, whereas before they were condemned to be silent. These characters of Attars also express their opinion about creation, about the distribution of goods and food, and the manner in which they are treated by God. They express their opinion in a strange way, pessimistic and bold, even insolent."

--Helmutt Ritter, "Muslim Mystics Strife With God."

Thursday, May 1, 2014

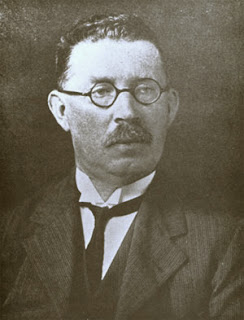

Hellmut Ritter, 1892-1971

From the Encyclopaedia Iranica: German scholar of Islamic studies, and particularly of Persian literature and mysticism. His magnum opus: Das Meer der Seele: Mensch, Welt und Gott in den Geschichten des Farīduddīn ʿAṭṭār (Leiden 1955) is an encyclopedic manual which guides the reader through the psychology of Islamic mysticism. The book is the best introduction to date into Sufi thought.

Ritter's great essay "Muslim Mystics Strife With God" ends with this magnificent paragraph:

It is the task of a science which deals with man, with his religious feelings and philosophical ideas, to listen to people far off in space and time, and to try to understand their ideas. We study these subjects in order to get out of the narrowness of our own world, in order to see how men [and women] of other countries and ages have struggled for the solution of problems and endeavored to overcome the troubles, conflicts and afflictions which mankind has to face and will have to face in every place and at every time.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)